Musical Language

Howard S. Becker

(Paper given at the conference on “Fifty Years of Music Sociology in Vienna,” September 24, 2015, held at the Institute for Music Sociology, University of Music and Performing Arts, Vienna)

In the early 1950s, when I was a graduate student supporting myself playing piano, I substituted one night for someone who played in a trio that had a regular weekend job in a neighborhood bar on the southwest side of Chicago. The leader, a tenor saxophone player, was worried—he didn’t know me but had had to accept me because I was the only pianist he could find on short notice. After we played the first set, he bought me a beer, and then asked, casually (but I suspected something was going on), “Are you married?” I said I was. After a pause, he asked, “Got any kids?” I said I did. He asked, “How many?” I said one, which gave him the opening he was looking for. “If you had three kids, like me, you wouldn’t be playing all those modern chords, because people don’t like that stuff, you know what I mean? I need to keep this job, let’s see if we can get the right sound.” Like most young piano players around town, I habitually embellished dominant 7th chords with one or more raised and lowered fifths and ninths: to my ears a richer sound, to his ears a potential danger to his livelihood. I cooled it for the rest of the evening, because I did know exactly what he meant. I understood that a few altered notes in a chord carried just such meaning for him, so that he could express a complex argument in a few words based in a shared understanding of who understood and liked what kinds of music, an understanding resting on a language that could be expressed in technical musical terms as well as in ordinary English words.

When we go to another country, where people speak another language, we know we’ll do better research if we understand that language and better research yet if we speak it ourselves. If we go some place whose people speak a language no one in our country knows, we understand that the first thing we have to do is learn that local language.

We often fail to realize that we face the same problem within our own societies, where all sorts of sub-groups speak specialized languages most of the rest of us don’t know. Some ethnic groups speak the language of their country of origin, or perhaps a dialect not even all people from that country speak. Social classes in the same country, or people from different regions in it, often speak substantially different dialects too. And then our research requires us to do some linguistic study first.

We encounter similar problems studying occupational groups, which ordinarily have, at the least, a substantial technical lexicon, referring to things, activities, and situations the rest of us seldom or never encounter. When I interviewed schoolteachers in Chicago, for my dissertation research, I had no such problems. I had never taught in a school for children, but I had been a student in those Chicago schools, so we had common referents for the words they used describing their work situations and career strategies, especially when those words referred to matters most adults in the society they worked in were all familiar with.

When I studied medical students, I had more trouble. The students, and their teachers, used a lot of words I wasn’t familiar with, many of them technical terms referring to things I’d never seen (organs, muscles, nerves, bones) or conditions I knew by lay names. So I learned the medical names of some of those physical structures and learned to call a runny nose “rhinitis” and what I knew as hives “urticaria.”

I had to learn those things because what really interested me—the forms of collective activity that embodied “medical practice”—took place in that language. Sociologists know they learn a great deal about unfamiliar activities when something “goes wrong.” The reaction to someone’s “mistake” or “bad behavior” reveals tacit rules and common understandings members of that group accept as defining how they should behave. Something “wrong” tells you, by implication, what’s “right.” When a student or, better yet, a doctor “made a mistake,” I was less interested in the mistake than I was in what made it a mistake, which I found out by understanding the language people used to describe it.

Which brings us to music. Musicians talk about music in a language quite divorced from common language: special words for the physical and aural objects they use to make music, and for the kinds of sounds they make when they’re “making music.”

Players make those mistakes, so valuable to us as sociologists, in musical language, and their colleagues describe their errors in musical language. If you want to find these sociological gems, you must know musical language, both to hear what participants are referring to and to understand why they think it’s “wrong.”

Specialists in the sociology of music know all this. Many, probably most, of the people who write about music sociologically play or have played professionally or as serious amateurs. They read music, can discuss music in the technical language of the trade, and are also, commonly, familiar with the contingencies of musical careers and the intricacies of the organization of musical life. When they study music they know what the words and the musical sounds they hear mean.

I’m going to present two bodies of “data” to illustrate how this works in practice,. the first from the research Robert Faulkner and I did on players of American popular music (2009), the second from Simha Arom’s classic ethnomusicological study, La fanfare de Bangui (2009). Both studies illustrate, in different settings, how having or getting some musical knowledge made the research possible and productive.

Faulkner, Becker and Understanding Contemporary Working (Popular) Musicians

Faulkner and I centered our research on this question: how can several players who have never seen each other written music and who have no written music to consult, play for several hours for a more or less attentive audience without getting into serious trouble. We both had had plenty of experience in such situations, but now we wanted to understand it more generally, as a form of social activity.

The usual answer to our question—in fact, what we had thought was the correct answer—is that musicians rely on culture, a shared body of knowledge, to supply what’s needed to pull this trick off. But we soon realized that that answer wasn’t correct, because Faulkner occasionally observed situations in which, when someone “called a tune,” someone else in the group said they didn’t know it. That created a problem which the player who didn’t know the song often solved by saying “That’s alright, you play the first chorus, then I’ll play the second one.” Which only pushes the problem back a step. How did these musicians play songs they didn’t know?

I found the answer to that, which I more or less suspected (having often done it myself) but had never really thought about, when I spent an afternoon playing with Don Bennett, a very experienced bass player, in his San Francisco studio.

At one point, I asked him if he had ever had to play a tune he didn't know at all. He said that of course he had, everyone had to do that sometimes. When I asked how he did it, he looked puzzled and finally said that he wasn't sure. "But, I'll tell you what, let's try it and see what happens. Play something I don't know and I'll follow you and tell you what's going on."

I thought for a minute and picked a very obscure tune from the 1940s (I had probably learned it from hearing the Glenn Miller orchestra play it on the radio), "I’m Stepping Out With a Memory Tonight." No jazz great had ever recorded it, so it wasn’t likely anyone would know it that way. I told Don the name and he confirmed that he’d never heard it. I started to play, in the key of F. Don, as any bass player would, watched my left hand closely, to see what bass notes I was playing that he could pick up on. He had no trouble with the first four bars, a standard I VI II V progression. The fifth bar goes from the major chord on the tonic—in this case, FMaj 7—on the first two beats, to the same chord with an E in the bass. As soon as I played the E, Don said, "Stop right there. That's a clue." I said, "What's a clue?" "That E. When you play that, I know almost for sure that the next note is going to be an Eb going down eventually to a D. And that means the harmony is almost surely going to be F7 going to BbMaj7, maybe a Gm7. Then I’m home free."

As soon as he said that, I knew exactly what he was talking about, knew that I would have made essentially the same analysis of the possibilities he had made, and would have come to the same conclusion. And thus would have been able to play at least that part of the tune as he then did. (Although, being a bass player, he did not have to be able to play the melody.)

He added, "You know, there are clues to things like not only what the next chord will be but when you're going to play a big Las Vegas ending." (Faulkner and Becker 2009, p. 80)

The understandings he called on to perform this analytic feat deal with more subtle matters as well. Musicians such as we were often have a “feeling” that something “isn’t right,” that there’s something unfamiliar and awkward in something they’re playing. These awkwardnesses, like the mistakes I spoke of earlier, show the kinds of understandings and interpretive strategies make it possible for strangers to play together proficiently.

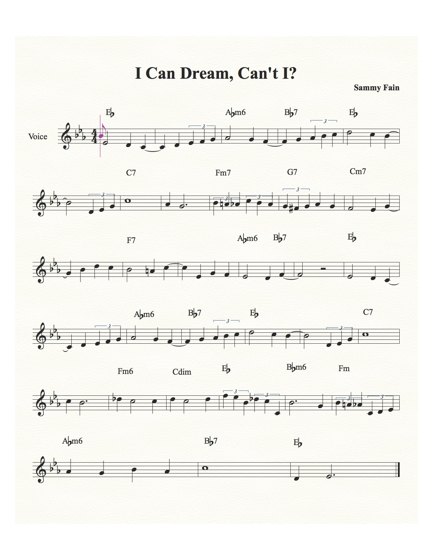

Faulkner came to visit us in California while we were working on the book and, of course, brought his horn with him. We spent an afternoon exploring unfamiliar tunes with Don Bennett. One was with “I Can Dream, Can’t I?” All three of us felt that there was something a little off-center about this tune when we played it from the music, something that made us uncomfortable, but that we couldn’t put our finger on. Don finally said that the problem was that the tune kept feeling like it was really in three [i.e. ¾ time], instead of four, so that when he played four [beats to the bar] behind us, the way the melody was laid out made it sound like it was “really” a waltz. We all agreed that that was what made us feel uncomfortable, unnatural, awkward, and made the tune hard to play. If we didn’t pay attention, we started drifting into playing it as a waltz.

He solved the problem by playing the first chorus in two [two beats to the bar], which interrupted the easy flow that made three seem natural, like what wanted to happen. As soon as he did that, everything fell into place and we all felt comfortable with it. Except for the very last bar, where the melody comes to rest on the second beat, rather than the first beat, where we all felt it “should” end. That is, where the normal expectations that made it easy for strangers to play together would have had it end.

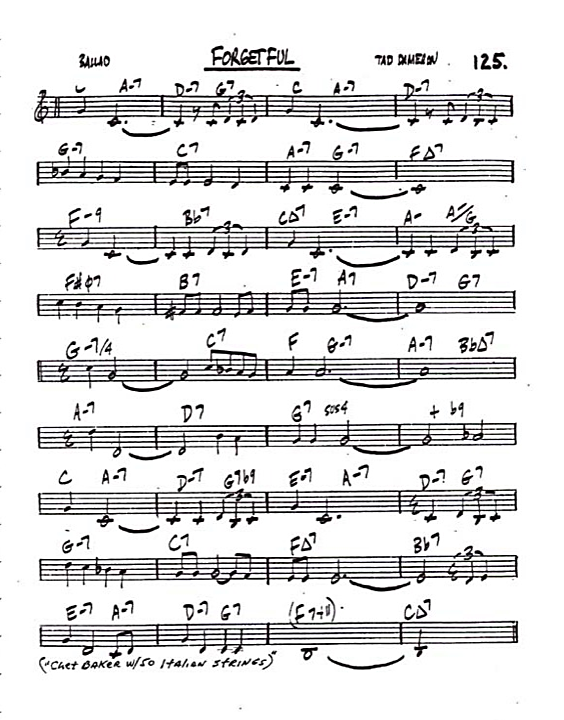

The other tune that seemed especially interesting was Tadd Dameron’s “Forgetful,” a tune I brought to our attention because I remembered it from an old Boyd Raeburn recording, and then discovered in one of the fake books I had, so that we had a lead sheet to play from. What’s particularly interesting about this tune is that its last section—it’s essentially AABA’, so I’m talking about A’—is twelve bars long instead of eight, but it doesn’t feel like the last four bars are a tag. We all recognized that there was something odd but didn’t discuss it a lot because, despite this anomaly, it flows absolutely naturally and you don’t feel a hitch or a lurch there when you play it.

Here’s why “Forgetful” seemed strange. Ordinarily, when a song has four extra bars at the end, it takes the form of a “tag.” The song comes to a perfectly ”natural” end in a standard cadence that indicates “finished,” but at the last minute prolongs the end by modulating to, say, the VI7 chord (if you’re in C, the final C major chord descends to an A7 and then around the circle of fifths to a final cadence ending on C major). “Forgetful” doesn’t do that. It has no false ending turning into a dominant seventh somewhere else. Its extra four bars are inserted earlier in the last strain, in a way that seems natural, so that the last section of the tune consists of three four bar phrases, all of equal importance. There’s no tag and yet there are four extra bars you can’t “account for” in any conventional way. They don’t create a “problem,” because they don’t throw you off and make you uncertain about where you are. But they do feel “unusual” and perhaps a little disquieting.

Ordinarily, the tunes we played came in a few standard sizes and shapes. There’s the AABA or AABA’, four eight bar phrases, the first two alike, then the “bridge,” and finally back to some version of the first eight. The A sections differ only in the turnarounds (“turnaround” deserves a little essay of its own); the bridge is usually quite different. Some of the tunes players liked involved substantial key changes in the body of the tune: leading up to the bridge or in the first few bars of the bridge, sometimes later in the bridge, or sometimes two key changes in the bridge. Other tunes have a slightly different version of this 32 bar format, for instance, ABAB or ABAB’, with similar possibilities for key changes.

None of these confused anyone with even minimal experience of the conventional 32 bar structure of most popular songs of that era. When you improvised you always knew where you were in those 32 bars. Similarly with the even simpler twelve bar blues form. But an occasional song wasn’t like that. A subclass of songs perfectly normal in other respects was only 20 bars long (“Bidin’ My Time,” “I’ve Grown Accustomed to Her Face,” “Keepin’ Out of Mischief Now”), built up in four, rather than eight, bar segments. We played these less often.

Something similar happens in “I Can Dream, Can’t I?” The construction of “ordinary tunes” puts the accents on beats where we expect accents to fall (1 and 3), and so don’t mislead players about the time signature. “I Can Dream” proceeds in phrases including triplet quarter notes which, while they are written in 4/4, have a natural 3/4 rhythm. If we let ourselves be lulled by “what’s natural,” we end up with a different (and, in the context, confusing) time signature.

Well, so what? You can’t play tunes that don’t fit the standard forms inattentively, the way you can play more “normal” songs. If you aren’t careful you get lost and that makes it difficult to sound like the band knows what it’s doing. To play together “professionally,” in a way that will not reveal that we have never played together before, all the players have to know just such things as which part of the song they’re playing now and what time signature they‘re playing in. If I’m playing solo and change time signatures or get lost in an unfamiliar structure, few listeners will notice, but if I’m playing with others, that kind of problem makes it hard for us to play together as though we had done this before, which is the impression we want to give to bystanders, whether we have or not.

So, to summarize, we found out what was going on musically that allowed us to play together without problems in several ways. Most importantly, we got people to explain to us how they did things that they had never verbalized explicitly to themselves. And then we analyzed, again with the help of our colleagues, what was going on when we felt ill at ease, felt that something was “not quite right,” and used those analyses in classic fashion to understand what we were doing when we played together unthinkingly in unproblematic situations.

We could not have done those things, made those analyses, without understanding the conventional musical language—of time signatures and keys and chords and circles of fifths—that we and our colleagues used to accomplish these small minor miracles.

Arom and the Music of Central Africa

Faulkner and I could arrive at our understanding of the conventions that let us play with others we hadn‘t played with before because we had learned all those things in another part of our lives where we weren’t sociologists. Does that mean that no one can study music and musicians who doesn’t know all that? No, it doesn’t. But it does mean that if we don’t know the relevant musical language when we start we should know it by the time we’re through.

Which is what ethnomusicologists have to do: find out how some other group’s very different way of organizing musical collaboration works. They have to find out all the things we did, prominently among them the basic musical language, that allow people to collaborate easily and gracefully in a system completely different from the Western tradition. Ethnomusicologists’ problems resemble those Faulkner and I had, but they solve them differently and the analytic problem is far more difficult.

Years ago I read a book, very relevant to these concerns, called La fanfare de Bangui, written by Simha Arom, a horn player in the symphony orchestra of the Israeli broadcasting system, who had unexpectedly and unintentionally found himself required to become an ethnomusicologist (a field in which he turned out to be highly gifted).

The title of the book needs a little explaining. In French, fanfare refers to what English speakers call a brass band. The president of the Central African Republic (whose capital is Bangui) had heard a brass band during a visit to Israel, and he wanted to have one just like it. He told his friends in the Israeli government what he wanted and for their own geopolitical reasons (they weren’t interested in spreading that form of musical culture for its own sake!) the Israelis decided to help. Somehow, Arom the horn player seemed to some responsible party to be the person who could go to Bangui and satisfy the president’s wish.

And so Arom found himself there, where he quickly learned that the job couldn’t be done. What he needed to do it—instruments, musical scores and parts to play from, a pool of trained instrumentalists to play them—didn’t exist in Bangui. But there he was for a year, so he looked around for something else to do and soon learned that no one was collecting the indigenous musics of the many ethnic groups that made up the country’s population. He easily persuaded the President that a museum of the country’s music made a fine substitute for the fanfare and Arom’s adventure began.

It’s a long and wonderful story, but I’ll concentrate here on one of the major problems he had to solve: how to understand the music of an ethnic group called the Ngbaka (and eventually others like them). He finally learned to understand the music as the result and embodiment of a complicated system of understandings, simultaneously social and musical. Here’s how he got there.

He asked some of a village’s singers to sing a song for his recording machine, but what he heard puzzled him. The song

seemed to have no regular accents. I had no markers of the organization of the beats: I felt that there were measures (that is, the durations of the notes were proportional to one another), but I didn’t understand the standardization of the tempo. (78)

The singer he asked to record the same fragment again not only began in a different place, he didn’t sing the same thing at all. Was it the same song? The other musicians told Arom it was the same song but he couldn’t hear the similarities. He later learned that the songs were cyclic. You could start anywhere, and in fact singers usually did start anywhere at all. The words, being partly improvised, gave no clue to the form either. The singers’ descriptions and examples of what they were doing were even more confusing:

If the first singing of a song gave you four phrases (A-B-C-D), when you asked the same singer to repeat what he’d sung you’d hear C-A-B-B and D had disappeared. The next time he’d sing C-B-A-D and a day later, with him or someone else, it would be D-A-D-D. But all the singers in the village agreed that these were all the same song. (79)

Arom transcribed what he had recorded, but he couldn’t find where the pulse, the beat, was. And when he asked the musicians to clap the rhythm with their hands they always started in a different place in the song. He was looking for one stable version of the song but couldn’t find any such thing.

Finally, he recorded one version and then asked one of the musicians to listen to what he had played and clap his hands in time, while Arom recorded the two together on a second machine. That showed him that there was a beat underlying the song, though it was not expressed audibly.

On later visits to other ethnic groups in the country, using newly-available multi-track recording equipment, he elaborated the original idea into a complex method. First he recorded an ensemble. Then, having learned the order the players “entered” into the playing of that piece, he put earphones on the one who entered first, and had him play his part while hearing what the group had played together. Then he had the next one to enter listen to the player before him while playing his part. Arom recorded that and each succeeding pair until he could hear how each new entrant found his way into the developing ensemble. Then he had each player clap along with each of the parts. Which finally revealed to him the underlying regular pulsation which had remained implicit throughout. Though no one played it, they all (including Arom) felt it. He found what he was looking for in the pulse of the dance the music accompanied.

But the recordings taught him more. When two singers began to sing what they said was the “same” melodic line they quickly diverged, going in quite different directions, not just mere variations. There seemed to be an endless number of possibilities without any observable system organizing them. But the musicians themselves felt completely at ease with this apparently infinite variety, knew “where they were” at every moment, started and stopped playing at appropriate places.

He finally learned where to look for, and so discovered, the basic units: the “parts” (as in soprano, alto, tenor and bass, although they were not based on pitches), the four kinds of things that couldn’t be left out, which were assigned to specific people. And he discovered how to ask the people responsible for singing those parts to tell him which elements were “basic,” always had to be sung, and thus were what had to be respected—the way a jazz player might refer to the underlying “changes” of a song. As when jazz players would say, when they told someone who didn’t know Parker’s composition “Ornithology” not to worry, it was “really” the changes (the harmonies) for “How High the Moon.”

Arom used variants and extensions of this method to arrive at a more detailed and nuanced understanding of a variety of musics from around the country, many of which operated on more or less similar principles.

Here’s another example, taken from a later, more streamlined and knowledgeable study of the horn music of the Banda Linda, a music played by ensembles of eleven to eighteen players on horns made (for the upper registers) from antelope horns and (for the lower registers) from flared tree roots. Young boys learn from the older players and Arom was sure that as a horn player himself he could learn to play them. He asked to be taught as young boys were taught.

Each player entered separately and each seemed to play a different part. So he recorded the player who entered first, then asked to be taught that part, but asked the teacher to play its simplest version, the one they would start the child with. Then he asked the teacher to remove some notes, to simplify it even more, until the teacher refused, saying that if he took any more notes out it would no longer be his part of the song. Arom went through the same procedure for every part, until he had a complete, simplified model of the entire piece. From which he produced a score, on which he could mark the essential notes, those that appeared in these minimal versions of all the parts.

He learned from this exercise and from further questioning around its results that the horns were arranged in families of five, each member starting on one note of the pentatonic scale, and each family tuned in the same way an octave higher. As long as each note could be played somewhere, you had a sufficiently complete ensemble.

Then he had a large group play a piece, recorded it, and spent a long day transcribing each part. The next morning he announced that he was going to play the piece with them and, playing it many times, play each of the parts he had transcribed in turn. Since the players came in consecutively, one after the other, he knew that he could start playing the first part and know he had it right if the second player could then come in correctly. Then he played the second part to see if the third player would enter correctly. And so on until he had played every part correctly. All the players carried him around in triumph and then he bought a case of beer and they partied.

A Final Problem

Suppose that, like so many of us who study music sociologically, we’ve learned the relevant language for describing the musical activities we’ve investigated, the musical understandings the people we’re studying routinely rely on to coordinate their playing. We’ve used that knowledge to gather data, make observations, collect all the materials we’ll use to write a useful account of what we‘ve learned. When we write our articles and books, we’ll necessarily use the musical materials we gathered as evidence for what we have to say. (For this reason, I’ve included in an appendix lead sheets for the two songs discussed in the first part of this essay so that readers who know how to read such a document can inspect the evidence at their leisure.)

If our readers understand the relevant musical languages as we do, we can tell the story easily. It’s a conversation among adepts. But, if we want our work to reach a larger audience than those who already know enough to understand the technical matters we have learned—the musical forms and the notes, the written code, we’ve expressed them in—we somehow have to convey the technical knowledge that audience doesn’t have so that our argument will resonate for them. And I don’t speak here only of the lay public, but also of our sociological colleagues whose eyes also glaze over when they see bars of music in a text. How do we tell them what we’ve learned?

Some writers have described technical musical language with metaphorical descriptions. A well-known passage in E.M. Forster’s novel Howard’s End describes the andante in Beethoven’s Fifth symphony in a way that non-musicians understand. I’ll quote a small piece of it:

[T]he music started with a goblin walking quietly over the universe, from end to end. Others followed him. They were not aggressive creatures; it was that that made them so terrible to Helen. They merely observed in passing that there was no such thing as splendour or heroism in the world. After the interlude of elephants dancing, they returned and made the observation for the second time. Helen could not contradict them, for, once at all events, she had felt the same, and had seen the reliable walls of youth collapse. Panic and emptiness! Panic and emptiness! The goblins were right.

Her brother raised his finger: it was the transitional passage on the drum.

For, as if things were going too far, Beethoven took hold of the goblins and made them do what he wanted. He appeared in person. He gave them a little push, and they began to walk in a major key instead of in a minor, and then he blew with his mouth and they were scattered! (Forster 1910, p. 29)

Similarly, the American critic Whitney Balliet became famous for his lyrical, imaginative descriptions of jazz soloists’ playing in his essays in the New Yorker magazine’s non-musician readers. Here’s a sample, his description of the pianist Art Tatum playing something in the ”flashy, kaleidoscopic style” he used when playing for the public:

He would play a four- or eight-bar introduction, made up of an oblique variation of the melody. . . . Then he would go into eight bars of ad-lib melody, using single notes in his left hand and loose chords in his right, break this with a two-bar descending arpeggio, return to the melody for four more bars, insert a two-bar dissonance, and pick up the melody again. The eight-bar bridge would consist of a seesawing left-hand figure overlaid with a winding, ascending arpeggio, which, when it reached its top, would pause, then fall down the other side of the mountain, landing in a flush of single notes and a two-bar double-time coda. (Balliet 1986, p. 206)

The elegant metaphors of these excerpts give readers very little factual musical information. If your research deals with the kind of cooperative musical activity my earlier examples described—if you wanted to report how the members of a string quartet discussed and decided on the bowing of a difficult passage—you couldn’t convey your results in this kind of language.

But, if you describe a musical event or conversation in the technical detail needed to understand what the people in those examples mean, you lose readers who understand neither the problem the musicians are talking about or the solution they arrive at. And so don’t—can’t—understand the point of the example or its analysis.

I won’t say that these passages convey no information, but they don’t report the detailed technical understandings that infuse musicians’ talk as they negotiate the day-to-day contingencies of performing in public, the kinds of things Faulkner and I, and Arom, had to report.

The alternative is to explain the technical matters in simple language non-musician readers will understand sufficiently to grasp the sociological points being made. Faulkner and I made that choice when we chose, as an example of how unfamiliar harmonic patterns destabilize jazz players and create difficulties in achieving concerted action, John Coltrane’s well-known composition “Giant Steps,” which, we said;

creates just such a problem for players accustomed to II-V-I sequences because, though its harmonic structure builds on the same II-V-I sequences, it does so in an unfamiliar way. Consider the first three bars of “Giant Steps”:

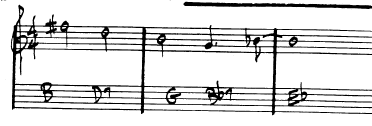

The first harmonic move, from a tonic chord to a dominant seventh chord a minor third above it (B to D7 here), is not unknown in standard tunes, though not very common. (The move to the dominant 7th a major third above, leading to a circle-of-fifths sequence arriving at a conventional final cadence in the original key, occurs more frequently.) The second move, from D7 to GMaj, completely conventional in itself, however, doesn't end on a dominant seventh, leaving the cadence unresolved. Instead, ending on a major chord, it firmly changes the key to GMaj, and then immediately repeats this move, going up a minor third to Bb7, and changing keys again, V-I, to Eb. (Faulkner and Becker 2013, pp. 126-7)

We were not surprised that many readers found this heavy going, and feared that such extended remarks would frighten potential readers, but could think of no other way to explain and exemplify a key component of our understanding of what lay beneath and fueled some of the conflicts and discomforts musicians experienced in the historical shift from be-bop to post-be-bop performance.

A few final observations. We can, of course, approach many topics in the sociology of music—studies of audience participation in musical events, studies of the organization of the industries built up around music, for instance—without any of these problems. As long as participants in the actions that interest us communicate in ways that don’t require technical language, neither do our reports and analyses

Nor does a sociology of music have a monopoly on these problems. The sociology of science shares many of these difficulties, requiring as it often does a substantial understanding of scientific procedures, specialized vocabularies, and mathematical knowledge we cannot count on our colleagues to have. This is probably an inevitable concomitant of the growth and increasing specialization of sociological research.

References

Arom, Simha. 2009. La fanfare de Bangui. Paris: La Découverte.

Balliet, Whitney. 1986. American Musicians: 56 Portraits in Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press.

Faulkner, Robert R. and Howard S. Becker. 2009. Do You Know . . . ? The Jazz Repertoire in Action. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Forster. E. M. Howards End. 1989 (1910). Penguin Classics: London

Musical Examples

|